http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/3374.html

Monday, July 25, 2011

You have received a shared article

http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/3374.html

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

The Lean LaunchPad at Stanford – The Final Presentations

Class lectures were over last week, but most teams kept up the mad rush to talk to even more customers and further refine their products. Now they were standing in front of us to give their final presentations. They had all worked hard. Teams spent an average of 50 to 100 hours a week on their companies, interviewed 50+ customers and surveyed hundreds (in some cases thousands) more.

(p.s. they’re going to make a company out of this class project, and they’re hiring engineers.)

- The combination of the Business Model Canvas and the Customer Development process was an extremely efficient template for the students to follow – even more than we expected.

- It drove a hyper-accelerated learning process which led the students to a “information dense” set of conclusions. (Translation: they learned a lot more, in a shorter period of time than in any other entrepreneurship course we’ve ever taught or seen.)

- The process worked for all types of startups – not just web software but from a diverse set of industries – wind turbines, autonomous vehicles and medical devices.

- Insisting that the students keep a weekly blog of their customer development activities gave us insight into their progress in powerful and unexpected ways. (Much more on this in subsequent blog posts.)

- In this first offering of the Lean Launchpad class we let students sign up without being part of a team. In hindsight this wasted at least a week of class time. Next year we’ll have the teams form before class starts. We’ll hold a mixer before the semester starts so students can meet each other and form teams. Then we’ll interview teams for admission to the class.

- Make Market Size estimates (TAM, SAM, addressable) part of Week 2 hypotheses

- Show examples of a multi-sided market (a la Google) in Week 3 or 4 lectures.

- Be more explicit about final deliverables; if you’re a physical product you must show us a costed bill of materials and a prototype. If you’re a web product you need to build it and have customers using it.

- Teach the channel lecture (currently week 5) before the demand creation lecture (currently week 4.)

- Have teams draw the diagram of “customer flow” in week 3 and payment flowsin week 6.

- Have teams draw the diagram of a finance and operations timeline in week 9.

- Find a way to grade team dynamics – so we can really tell who works well together and who doesn’t.

- Video final presentations and post to the web. (We couldn’t get someone in time this year)

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Cash is king: 8 tips for optimizing your startup financing strategy - Fortune Finance

Cash is king: 8 tips for optimizing your startup financing strategy

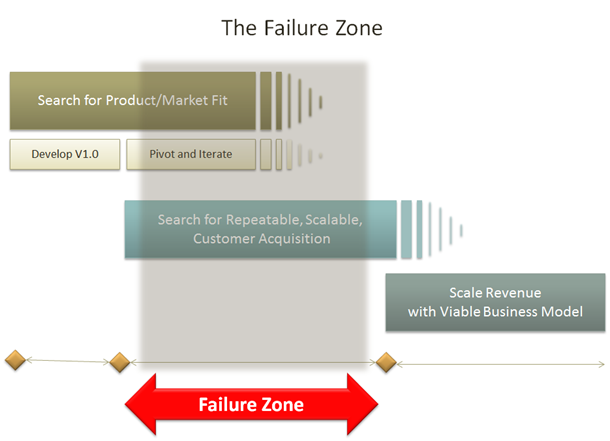

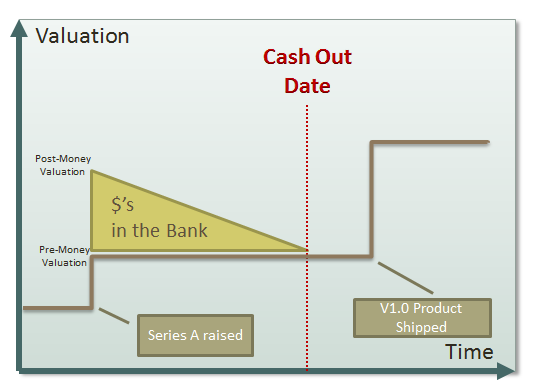

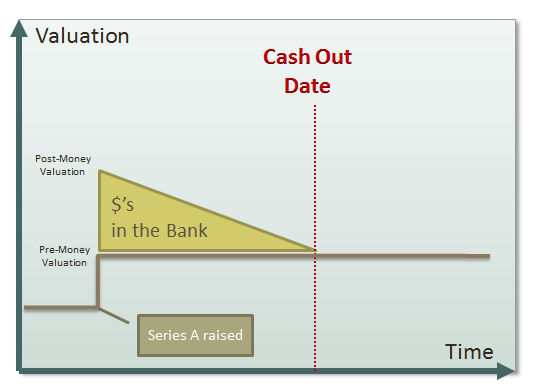

- Make sure that they understand when their cash runs out

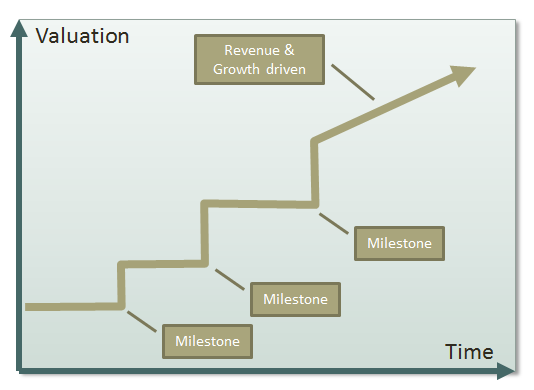

- Understand what milestones have to be achieved to get a higher valuation

- Create the right plan to achieve those milestones in the right timeframe

Usually the single biggest way to show that risk is being reduced is to show evidence of increasing traction with paying customers. If a significant number of customers are willing to pay for a product, that tells an investor many positive things:

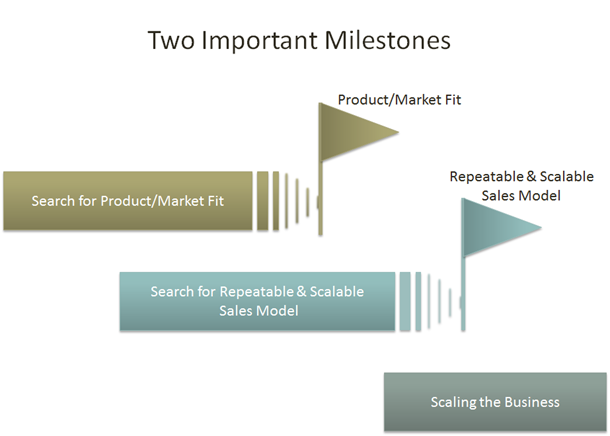

- The company has reached product/market fit

- The monetization strategy is working

- The technology works

- The team has shown some ability to execute

- You have shown a wireframe mockup of the application to a significant number of customers and they are willing to talk to investors and tell them that they plan to buy the product when it ships.

- You have shipped a beta of the product to some customers

- Your beta customers are testing the product and reporting success

- You have a large number of free users, and their engagement with the product is high

- You have sold the product to a small number of paying customers

- Your paying customers have put the product into production usage, and are reporting success

- Your customers are coming back and re-ordering, and recommending the product to their friends

Readers of one of my earlier blog posts, Setting the Startup Accelerator Pedal, will know that I like to think of the lifecycle of a startup in three phases. The first phase is the search for product/market fit. Increasing customer traction is the best way to prove to investors that you have reached product/market fit. The second phase is the search for a repeatable and scalable sales model. Reaching this milestone will greatly increase valuation and attract growth stage investors who like to invest in companies that are ready to scale.

- Hiring a great CEO with a proven track record

- Hiring a strong management team

- Reaching profitability

- Becoming the clear market leader

2. Identify your specific risks

- Team: unproven team. Not clear if they can execute.

- Competitive: crowded marketplace with significant competitors

- Market timing: you're confident about the long term market prospects, but it is not clear when the market will take off.

3. Look for quick ways to litigate risks before fundraising

- The best example of this would be a company looking to raise a Seed or Series A round. Even in this early stage of the business, any proof of customer traction can greatly de-risk your startup and increase valuation. This could be accomplished by sketching wireframes of the application, and showing them to customers. The goal would be to get enough customers to validate that this meets a real need so that they are keen to start using it as soon as it ships, and willing to pay for it. If you were able to walk into an investor meeting with a list of 20 customer that were willing to talk to investors, or had provided you with a written statement to that effect, your chances of getting funded would go up substantially, and your valuation would likely increase.

- In our battery example above, the major risk was technical. A quick way to mitigate the risk (but not totally eliminate it), would be to get the top technical expert in the particular area of science to take a look at the scientific problem you were aiming to solve, and have them render an opinion that this technical approach should work.

4. Either aise enough cash to match the milestones...

5. ... or match your milestones to available cash

- Reduce your burn rate to allow you to complete the milestone before you run out of cash.

- Pick a different intermediate milestone, and ask investors if reaching that will allow you to successfully raise an up-round.

6. Validate your milestone / valuation targets with investors

7. Focus all energies on reaching those milestones

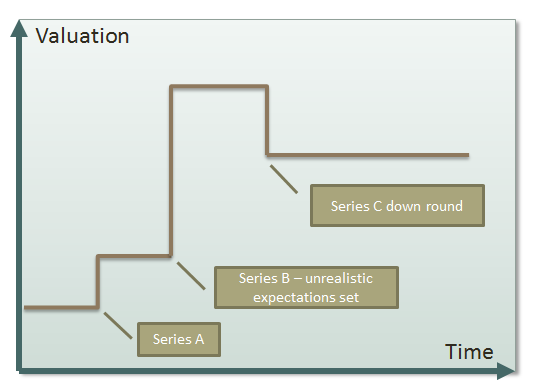

Sometimes down rounds can be caused by raising money at an unrealistic valuation that can't be justified no matter how good the execution. Entrepreneurs who have lived through bubbles understand this well.

Conclusion

My goal was to highlight how startup valuations change based on milestones that significantly de-risk the business. Armed with this information, entrepreneurs should talk to investors to understand how they see the risks and milestones. Then plan and manage their business around achieving desired milestones before hitting their cash out date.

- Take the time to think this through and build a plan.

- Make following the plan a very high priority.

Tuesday, March 8, 2011

Fwd: Forbs: Clayton Christensen: The Survivor, As told to David Whelan 03.14.11, 6:00 PM ET

From: Kwanrat Suanpong <kwanrats@gmail.com>

Date: Tue, Mar 8, 2011 at 3:02 PM

Subject: Forbs: Clayton Christensen: The Survivor, As told to David

Whelan 03.14.11, 6:00 PM ET

To: kwanrats <kwanrats@gmail.com>

On The Cover/Top Stories

Clayton Christensen: The Survivor

As told to David Whelan 03.14.11, 6:00 PM ET

Clayton Christensen, 58, is one of the most influential business

theorists of the last 50 years. The Harvard Business School

professor's 1997 book, The Innovator's Dilemma, introduced in elegant

terms the notion of "disruptive innovation," which explains how

cheaper, simpler or unexpected products and services can bring down

big companies like U.S. Steel, Xerox and Digital Equipment. Every day

business leaders call him or make the pilgrimage to his office in

Boston, Mass. to get advice or thank him for his ideas. A consulting

firm he started popularizes his work, while a hedge fund run by one of

his sons puts money to work betting on disruptive technologies.

One industry that always eluded Christensen's influence was health

care. Caregivers and insurers told him his theories didn't apply to

their complex industry. Christensen knew they were wrong. His

investigation culminated in his 2009 book, The Innovator's

Prescription, written with two doctors. It exposed the many ways

health care was broken and recommended numerous ways it can be

systematized and disrupted the same way mainframes gave way to PCs and

now iPhones.

Christensen's work took on new urgency the past few years as he

suffered a heart attack followed by cancer followed by a stroke. For

Christensen it was not a reason to get too upset. It was another

opportunity, in a lifetime full of them, to gain insight into how to

make the world work better. Because of his July stroke it took a long

time for Christensen to be ready to sit down with FORBES. He was in

intensive speech therapy, eight hours a day at the beginning. But he

graciously agreed to tell his inspiring story in January, the same

month he went back to teaching. Here it is in his words, along with

those of his family, friends and close colleagues.

Clayton Christensen

My dad died at age 49 from Hodgkin's Lymphoma. A wonderful dad. Even

back then in 1975 the probability that it would go into remission was

about 80%. So I happily went off to Oxford. Once I was there for six

weeks it was clear that he was in trouble. The Rhodes Trust was just

marvelous. I went to talk to the warden Sir Edgar Williams and after

two minutes he said, "We'll send you home. You can come back next

week, next month, next year, ten years from now." I was with my dad

for the last two months before he died. It was the most wonderful,

happiest experience of my life to take care of my dad.

He worked for a department store in Salt Lake, ZCMI. As we were

growing up he took us to work on Saturday to help him put the food on

the shelves. I knew his job pretty well. I kept it up [after he got

sick]. That kept us on the same salary and insurance. He dictated to

me his life history. Most I'd heard before. I put it together into a

biography. It's been a wonderful thing. As my kids grew up, on Sunday

morning I'd say, "Okay, guys, read pages 20 to 30 in Grandpa's

biography, and let's talk about what it means for us."

My mom also died of cancer. She was 82. That was just about five years

ago. In the Mormon Church we believe we can be married for all

eternity, not till death do you part. As Mom was getting older she was

excited, truly excited, that within a few years she'd be with Dad

again. I've known people who wanted to die, but most of them were so

miserable they wanted to escape it. But in this case my mom was

healthy. She didn't want to live too long that she couldn't take care

of herself. She was so excited when her doctor said that she had

pancreatic cancer and likely would only live six or seven weeks. She

had a great life and a great family. "Now I can see your dad again,"

she told me.

Ann Christensen (oldest daughter)

My dad is a perpetual student. He'd come home from work every day

excited about some comment a student had made or a paper they had

written. He'd say, "You'll never believe what I learned today." It

turned into dinner table conversation.

Matthew Christensen (oldest son)

Too many of his former students who come back, too many people period,

say family is important or my religious beliefs are important. But if

you look at how they spend any given week, they spend 90 hours at

work. They leave before their kids wake up and come back after they go

to sleep. When my dad was at the Boston Consulting Group, he would go

in superearly and come home early. He was famous for leaving early. We

would play catch in the daylight.

Diabetes

Clayton

I got Type 1 diabetes at 30. It hit me in 1982 when I was a White

House Fellow in Washington. I had viral pneumonia. I lost 35 pounds in

six weeks. And I couldn't see anything. Everything was blurry. I was

always thirsty.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Matthew

One time we visited my mom's sister in Charlottesville. My mom is the

oldest of 12 children, 9 boys. My dad drank a full 2 liters of Seven

Up at dinner. My mom thought that was rude. She was upset. He was

always thirsty.

Clayton

I called a friend who was a doctor in Boston, and he immediately

diagnosed it: "Oh, you have diabetes." I called my wife and said, "Oh,

Christine, I am so relieved I have diabetes. I thought I was going to

die of cancer."

Diabetes is a great example whereby giving the patient the tools you

can manage yourself very well. It's been 28 years. If you have too

much insulin your blood sugar drops and your brain shuts down. I've

only lost consciousness four times in all of those years. The reason

is that I test my blood sugar seven times a day. If it's too low I

have a Snickers bar. If it's high I take a shot. And sometimes I am so

desperate for a Snickers bar I give myself insulin so I can have one.

I figure if I live a normal life I will take about 90,000 shots.

FORBES

The tips of Christensen's very large fingers are covered in black

speckles from the pricks he gives them to test his glucose levels.

These sorts of inexpensive, at-home care devices (Christensen has also

used insulin drug pumps) are the kind of disruptive innovations the

health care system needs to move out of the costly hospital and

medical office setting. Disruption can replace a business that

provides a service with a network that allows people to do it

themselves. You download songs and make your own playlists now instead

of depending on labels to create albums and market them. In medicine

this might mean going from relying on your doctor to keep track of

your diabetes, which he likely has little time to do, to instead

plugging in to a network of other diabetics who can share tips and

provide tools to manage it yourself. Websites like dLife represent

this future. Crohns.org provides tools and facilitates support for

managing that chronic digestive disorder.

Grant Bennett (friend for 32 years)

Overnight Clayton became an insulin-dependent diabetic. He would chart

readings on a sheet of paper. He'd have an upper and lower control

limit, trying to keep as close to the midpoint as possible. My

daughter is an M.D. She says, "The most disappointing part of my job

is people who return to the ER again and again and you tell them what

to do and they don't do it." He's at the extreme opposite. In the

middle of a meeting he would prick himself, test his blood, and then

inject himself in his arm or abdomen.

Matthew

He's a huge, indestructible guy. He's bigger than all the other dads

[at 6 feet 8 inches]. He's had diabetes, but as a consequence of that

he's very careful about what he eats. He would play basketball

Saturday mornings at church.

Ann

When you're in elementary school in public school in our town you have

to write research reports. My siblings and I each did a research

report on diabetes for school.

Heart Attack

FORBES

In November 2007 Christensen had a massive heart attack while the book

The Innovator's Prescription: A Disruptive Solution for Health Care

was in its final stages as a manuscript.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Clayton

It was very strange because there was no evidence of any narrowing of

my arteries. They were wide open. My bad cholesterol level is half the

normal level. And my blood pressure is always on the low side. But a

clot came from somewhere.

For seven years I was one of ten people who have responsibility for

the Mormon Church in the northeast quadrant of North America. Almost

every week I had to go to a city where all of the churches in the area

[known as a "stake"] came together to have a conference. My job was to

help them be better Mormons.

I got assigned to go to Montreal. The stake president in Montreal was

a physician. We stayed at his home. At the meetings on Saturday the

feeling of the spirit of God in that room was deeper than I have ever

felt in my life. It was extraordinary. You walk out of it just

committed to improve your lives for better.

We were sleeping in the extra room in their basement. At about 3

o'clock in the morning I just had a horrible pain in my chest. I never

had a heart attack before. This was something bad. I was thinking, if

I wake Christine and tell her, she'll wake the stake president and

they'll take me to the hospital. It's going to mess up a wonderful

meeting on Sunday. And there are 1,000 members of the church who are

going to come to that meeting. So I knelt down at the side of the bed

and I said to God, "I have a problem. Whatever this is could you

please just make it go away?" And it went away. I fell asleep and the

meetings on Sunday were comparable to the ones on Saturday. The

meetings ended about 9 p.m. on Sunday night, so then we started to

drive back to Boston.

The next day was Veterans Day. I went and raked up the leaves. About 4

p.m. in the afternoon I had a horrible pain. [Christensen still hadn't

told his wife about the episode the night before.] Christine was on

the phone. I grabbed my briefcase because I need to have something to

do when I'm waiting. I said to Christine, "You need to drive me to the

hospital." We started to drive and she said, "What are we going to the

hospital for?" I said, "I think I'm having a heart attack."

She said, "Let me take you to the firehouse, there's an ambulance

there." So we went there and knocked on the door, and she said, "Could

you take my husband into the hospital?" Within about 30 minutes of

when the heart attack occurred we were there.

A clot had come from somewhere and completely blocked the left

anterior artery, which is the major source of blood for the pumping

muscles of the heart. So they sent a catheter up into my heart and

just sucked it out. And as soon as it was gone the flow returned. If

the heart attack happened to me when we were driving home in the

middle of the night or if I'd been on an airplane I would have been

killed.

Dr. Ryan Thompson (Christensen's internist)

It was a major heart attack, the kind that leads to fatalities. It

required immediate stenting. It was the real deal, the so-called

widowmaker. Around a quarter of those who get those don't make it.

Clayton

I told my doctor [about the event in Montreal], and they were so mad

at me. I think God wanted the members of the church to have a great

experience, and he took care of me, too.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Matthew

Our offices were in Harvard Square. I got a call from my mom, who's

crying. She says, "Meet me in the emergency room at Mount Auburn" [a

community teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard]. He had his

briefcase, papers to grade or articles to write. He is horrified about

wasting time. It was a total shock. He had a stress test in June and

had gotten an all clear. And he was supposed to have cataract surgery

that Friday and had a pre-op checkup the Thursday before where he'd

been given an all clear. When your image of your dad is this

indestructible guy, even when you're 30, that's how you think of him.

Seeing him wheeled in on a gurney. It's an image of vulnerability.

Ann

They went in and removed the clot and reinforced the area with a

stent. The doctor came in to debrief us. He got caught a little

off-guard because we [she and two of her brothers] just started

peppering him with questions. We've all been consultants at different

firms, for companies that make those stents. We knew enough at that

point to be relieved. One of the stories that has always been in his

lectures is the impact of angioplasty on cardiothoracic surgeons [how

it disrupted open-heart surgery]. On some level that was comforting,

though we were all still very rattled.

Dr. Jason Hwang (coauthor of the Innovator's Prescription)

With angioplasty you blow up a balloon [in the artery] and it breaks

up a clot. Angioplasty started with balloons that didn't work that

well because the vessel would clamp down. It had a very high failure

rate. But then you added stents to reinforce the vessel, and then

drug-coated stents, and the technology of angioplasty marched upward.

As it gets better it can get more expensive, which opens the door to a

new disrupter.

Matthew

In general I don't think we have big complaints about his care except

for one thing. When he left the hospital he had been put on

medications. When we were waiting to go, for three or four hours, bags

packed, [we] waited for the nutritionist, who never came.

At home my mom had a husband who had just had a heart attack. She was

giving him salads, steamed chard and green leafy vegetables. Those

counteract the effects of Coumadin [a blood-thinning drug]. He went to

his first follow-up, and the INR [a measure of blood thickness] was

supposed to be between two and three. The first reading was a five. We

all have plenty of graduate degrees, but we were fumbling our way

through the dark.

Clayton

The problem from the patient's point of view is that we don't know

what we don't know and therefore we don't ask what otherwise we would

want to ask. When you have handoffs from many to many, as in a

hospital, the probability that things fall through the cracks are just

high. It has nothing to do with how good the individual people are.

Matthew

When he was at Boston Consulting Group [Dad] studied the Michigan

Manufacturing Company. It had nine auto parts plants. One in Pontiac,

Mich. had a mission to make any product for any customer. So you could

run the steel through different types of machines in any sequence. It

had about 20 different sequences and it was expensive. At the other

end of the spectrum was a plant in Maysville, Ohio that just had two

pathways. It could make parts at a very low cost. A hospital is like

the Pontiac plant.

Clayton

As we did the study we realized that every time you double the number

of pathways you raise overhead by 30%. It was not that the Pontiac

plant was badly managed. It just had a different mission. When I

present a diagram of the plants' pathways to a group [with arrows

between machines], I ask: "What if I took the names of the machines

off? Is it still a diagram of an axle plant--or a hospital?" Our

research has found 125 different pathways through a hospital. That's

why 85% of hospital costs are overhead.

FORBES

After his heart attack Christensen bought a home INR meter, which

measures how long it takes for blood to clot, so he could learn how to

manage his Coumadin.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Clayton

The other option is to go down to the hospital. You sit there for 15

minutes, and then they draw the blood out. And they never say, "Sit

here for five more minutes, and we'll tell you the result." Instead

they put it over in the queue. Ultimately they do the sample, and then

the result gets printed out on a sheet of paper. And what happens to

that? Sometimes it goes to my personal doctor, who may or may not see

it, or might see it and not know what initiated this in the first

place. "Should I call the patient, should I go see him or pull him

in?" The data doesn't go to the person who knows exactly what to do

with it. It helped me understand how wonderful and critical it would

be to push care closer and closer to patients and their families.

FORBES

Christensen argues that hospitals should focus primarily on what he

calls intuitive medicine, the process of figuring out what's wrong

with a patient. Once the treatment is set and can be routinized, that

care should be transferred to lower-cost providers. The best way to do

this is to have an integrated system, like what Kaiser Permanente runs

in the western U.S., where the hospital owns the outlying clinics and

surgery centers--and, ideally, also provides insurance. With more

routinized care, nurses can be trained to do doctors' jobs and

specialty facilities can focus on driving out inefficiency with

high-volume surgeries. Better and simpler diagnostics, like a

home-pregnancy test, would allow patients to better care for

themselves. Over time more medical care will follow the path of

treating infectious diseases, which in the past might have required

hospitalization but now can be treated with a prescription from a

nurse.

Clayton

If my INR is above three the result is Christine makes kale soup,

which makes your blood clot much faster. If it's low then we don't

have those kind of green vegetables. On-the-spot care works if you do

the test yourself, because that information causes you to do something

different.

Ann

After the heart attack Dad went through a very careful, deliberate

process with all of us and his assistant, thinking about all the

things he was involved with and where he could cut back. He definitely

wasn't able to travel as much. But that let him be at home in Boston.

He was able to work on the health care and education books. You want

to say he was stressed and if he's less stressed it won't happen

again. He works hard, but he's not a stressed-out guy. There's a

difference.

Grant

Clayton works very, very hard. As his consulting career took off he

traveled a great deal. He was always a very dedicated husband and

father. But over the years we'd have conversations about the

fundamental lifestyle questions. When Clayton had the heart attack,

the thought running through my mind is that this may be the one event

that may cause Clayton to slow down and not travel as much.

Cancer

Clayton

I was in Washington [in December 2009] with Christine. The church has

a temple there on the Beltway, and at Christmastime they have jillions

of lights decorating the gardens. We got invited to come down for the

ceremony. That night we stayed near Reagan Airport, and at about two

in the morning I had this awful pain in my lower back. I tried all

kinds of different positions. Nothing seemed to help. At three I went

down to a 7-Eleven. I got a bunch of ibuprofen. That didn't work. When

I was a high school senior I had an infection in my kidneys. And this

thing felt exactly like that felt. So we came home on the first plane.

I went immediately to a MinuteClinic. I thought, "I'll just get a

urine test." It turns out in Massachusetts that MinuteClinics can't do

that. We had to go to Mount Auburn Hospital, the same place we took

care of my heart attack.

FORBES

Christensen has advocated for the retail clinic concept, where care is

delivered in the back of a CVS or Walgreens. There's a menu of

conditions on the wall, like pink eye and poison ivy, and a simple

treatment protocol for each. Why shouldn't nurse practitioners and

other professionals like pharmacists, optometrists and

nurse-anesthetists be given more responsibility? They can deliver care

more cheaply than doctors.

Clayton

[The hospital] did the test. There was nothing that suggested

infection. The head of the emergency is the same guy who orchestrated

the care of my heart attack. He started to feel my side. And

basically, without telling me, he thought there was something big

inside of me. He thought it was my aorta that had ballooned up. They

very quickly did an ultrasound. They were all ready to cut me open and

deal with an aneurysm. But the ultrasound showed that it wasn't an

aneurysm. He said, "I have some good news and some bad news. The good

news is you don't have an aneurysm. But you do have really big masses

in there that feel forever like tumors." So he said, "I'm sorry." He

was very kind.

FORBES

After consulting with Dr. Thompson and another physician friend,

Christensen transferred to Massachusetts General, a Harvard-affiliated

teaching hospital downtown. An oncologist met with Christensen that

afternoon.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Clayton

The tumor in my abdomen was the size of a ball this big [mimes a

football]. It was pushing against my back, and that's what I felt.

There was another one behind my sternum that was wrapped around my

esophagus and it hadn't yet started to squeeze things down, but it was

poised to do that. The third one was behind my clavicle. It was about

the size of a jewelry box. That's the one they biopsied.

Matthew

Ephraim Hochberg, he's the oncologist who oversaw all of my dad's

care, could not have been better. Hochberg told us, "From what you

described, let me tell you what it is." I remember the percentages

added up to 110%--70% lymphoma, with three different types; 20% lung

cancer. The others were, I think, sarcoma and small-cell cancer, or

testicular cancer. Metastatic lung cancer was the worst-case scenario.

Clayton

They started doing all these tests. But this time I think I was more

knowledgeable because The Innovator's Prescription had been out, and a

big theme of that is that the body has a limited vocabulary to draw

upon to express that there's a disease inside. There are many more

diseases than symptoms. There are over 50 types of lymphoma. Dr.

Hochberg, I love to listen to him. He describes how lymphoma respects

the boundaries [of the lymphatic system]. It would rarely do something

so rude as to invade another organ, which was great news for me. The

lymph system is comprised of all of these tiny little tubes throughout

my body that collect stuff. Now all of a sudden you have three big

masses, but they were within the system that controlled them.

Dr. Ephraim Hochberg (clayton's lymphoma specialist)

Ninety percent of people will have microscopic evidence of lymphoma in

their blood--90% of people. The question is why 99% of those people

never get lymphoma. I got a phone call from [Christensen's] primary

care physician asking if I could see a patient. When I went to meet

him it was in the surgical waiting room. He was being prepped for a

biopsy. He was, even at that point, remarkably composed and

well-spoken. Especially with the lack of knowledge of what kind of

cancer this was. Everyone was extremely calm. I don't know how much of

that calm and reserve stemmed from his personal faith and how much

stemmed from his faith in our hospital, but I suspect that much more

of it was the former than the latter.

FORBES

After the biopsy Christensen received a diagnosis of follicular

lymphoma. It looked like a slower-growing variety, which would be less

responsive to chemotherapy and more likely to be terminal.

Clayton

I thought about it. I knelt down and made a commitment to God: "I

think I probably have done things in my life that you wanted me to do.

And if in your judgment there's more work that needs to be done on the

other side, I'm happy to go. And on the other hand, if I can be more

useful by staying in this side my preference is to stay. I don't want

to leave my kids and Christine just yet." I felt good. I don't think

that it was in any way depressing. In God's interaction with Adam he

didn't in any way promise that it was going to be easy. Even if you do

the right thing, there's a lot more that you need to learn--and a lot

of learning comes from adversity.

Dr. Hochberg

[After some more testing] it turned out he had a variant of lymphoma

that we described in a research paper five years ago. The cells look

small, but the rate at which they divide as measured by another test

is quite high. So there's a potential that some might even be cured

with a more aggressive type of chemotherapy. So we went from "It's

incurable" to a rare subtype of common lymphoma.

Clayton

As a complete, independent event, when I showed up at Mass General and

they were doing a workup, I just made this observation. In my right

eye there is this curtain that comes across, and it's all gray. My

retina was detached. Right there is the Mass Eye & Ear infirmary. They

decided that I probably ought to get the retina re-attached before I

started the chemo.

It was just fantastic to see the technology. The laser is like a spot

welder. You can hear it. [He makes two gunshot sounds.] It creates

scar tissue that tacks it to the back of the eye. They suck out the

vitreous [jelly] from your eye and replace it with silicone oil. The

silicone molecules are huge. They're too big to go through these

little pinholes in the retina [and cause another detachment]. When you

look out through these massive molecules everything is fuzzy for a

while. But, holy cow, how can I complain when this is saving my

eyesight? Who are the guys who developed the silicone gel that's so

pure? Who's the first guy who had the guts to open up the eye and

stick this laser in and go bing?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FORBES

The surgeon who performed the procedure, a vitrectomy and laser

retinopexy, would have needed ten years of training to operate inside

the eye. These procedures should and will become commoditized. Lasik

surgery is retailed directly to patients and not covered by insurance.

Its price has dropped dramatically since its inception in 1995. In

Singapore technicians have supplanted doctors in reading annual

diabetic retina scans. A similar disruption, in dentistry, is the

Invisalign mouthpiece, which straightens teeth without orthodontics.

Prior to Christmas Dr. Hochberg prescribed a cocktail of chemotherapy

drugs plus Rituxan, a targeted antibody from Genentech. Christensen

began getting infusions every three weeks for four and a half months.

That spring semester he continued working, speaking and doing some

teaching on a reduced schedule.

Clayton

Dr. Hochberg wanted me to stay in the saddle as much as I could

because that keeps you from thinking about yourself. You go down and

hit bottom about seven days after the therapy, and then by ten days

after you feel great. When my father was suffering from a very similar

disease, after he had one of his rounds I went in and just sat by him

and said, "Dad, how are you doing?" And he said, "I had no idea how

sick you have to be in order to die." Chemo is a lot easier to

tolerate now.

FORBES

After the first two rounds of chemotherapy, Christensen had several

scans to see how the tumors had responded.

Dr. Hochberg

He had a dramatic response. His first scan he had a mass in his

abdomen of 14cm by 8cm. On the second scan it was down to 8cm by

6cm--so, volumetrically, about a 75% response. The last scan we did

showed the mass was down to 4cm by 3cm.

Clayton

It was actually really fun to see Dr. Hochberg. He let me in the

office, excited about what he was learning. He truly was energized to

teach it to me. He's a true scientist. So he would never exaggerate.

He showed me the data in such a very excited tone of voice. Before

Rituxan came along, you could say probabilistically for the population

that you're going to be in remission for 4.3 years. If you keep taking

Rituxan for maintenance, you've expanded the probability of it staying

in remission out to 7 or 8 years. Dr. Hochberg raises the possibility

that in my case it won't come back. As he looks at what's happening to

my particular tumors, they just seem to be disintegrated. But you

never know. If it doesn't ever come back, then you know you've been

cured. That's all you can really say at this point.

Dr. Thompson

The most striking thing with Clayton was when I once visited him in

the chemo unit. He's sitting there receiving the infusion that makes

you feel miserable. But he just wanted to talk about my family. It

made me feel like a million bucks. Most people would want to just

sleep. His hair came out, and he had some neuropathy, some nerve

damage to his feet. By and large he did well.

Clayton

One day before chemotherapy, I woke up in the morning and went

downstairs. There on the kitchen table was this framed photo that had

Matthew, Mike [my second son], Spencer [my third son] and then Matt's

little boy named Clay [who is two years old]. They all had shaved

their heads to show solidarity and took a picture. They framed it with

their locks of hair under the glass. It was very sweet.

FORBES

Christensen moved on to lighter-maintenance doses every two months.

These will continue for two years. Hochberg estimates that

Christensen's total cancer care might cost $150,000 or $200,000.

Rituxan costs $8,000 or $10,000 a dose, just by itself.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dr. Hochberg

Academic medicine is an expensive way to provide therapy. When he

needed integrated therapy with his retinal detachment and his

lymphoma, he could have a world-class retina doctor seeing him at the

same time.

We're beginning to take cancers and classify them into "This is a

particular genetic subtype, let's treat it this way," versus "This is

a complicated disease; we don't have good therapy; stay with the

diagnostic shop."

In an ideal world Clay's system would have folks coming through a few

diagnostic shops like a big cancer center. Then they'd find a great

doc near them who can provide their care efficiently in the community

with a plan that's set in place. I also remember a discussion in the

beginning with Clayton about the transportability of medical records

and whether or not a universal medical record of some type would have

allowed some simplification. We ended up doing a lot of repeat blood

work because the records of the Boston hospitals aren't contained in a

single place.

Stroke

FORBES

Christensen had been out of chemotherapy for three months. But on July

18, 2010, while giving a talk at 6:30 in the morning on a Sunday to a

church group, he suffered a stroke.

Matthew

The stroke was the most distressing. I was at the church meeting. And

one of the things that my dad loves to talk about in our church

meetings is how to share the Gospel with other people. Midsentence he

couldn't talk. It was nonsense. I tried to help him sit down and put

my hands around his arms. His face looked fine. We thought: "Gee, this

might be a low blood sugar thing." He keeps candy in his briefcase.

I'm feeding him Skittles and Snickers. After about ten minutes he was

not getting better. We tested his blood sugar. It was 325 [not low].

We went out in the hall. My friend Mike Preece [a neuroradiologist]

came out with us and gave him a neurological exam. He held Dad's hands

with his fingers and said, "Can you squeeze my hands?" He said, "Yes,"

but he couldn't do anything. I could tell just from Mike's body

language and the other doctors there [at the meeting], this is a

dead-serious situation. By the time we got to the hospital he couldn't

walk. I remember pushing him in a wheelchair, putting his briefcase in

his lap.

For someone that's always had the image most kids have of their dad

being Superman, and him having always been such an articulate person,

it was hard. You try to talk to him and he would say things and they

made no sense. I was thinking, "What's going to happen? Will he be

okay or not?" I think he's done so much and done so much good. What

else is there for him to do? The end comes for everyone. And could it

be for him?

FORBES

At Mass General Christensen, within an hour, received a clot-busting

drug called TPA, which has been shown to help minimize stroke

complications.

Dr. Thompson

There's nothing that unifies what happened to Clayton. Each is not

that uncommon. Stroke is the third-leading cause of death, heart

attack is number one, cancer is number two. But the chances that one

person would have all three is uncommon. Type I diabetes is a risk

factor for heart attack and stroke. But there's nothing unifying all

three.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FORBES

The stroke managed to avoid the part of his brain that controlled his

motor skills and analytical abilities. He did, however, lose his

speech. In a recent lecture to HBS students, he described the

sensation by comparing it to a file cabinet in his head filled with

words--that is suddenly tipped over.

Christensen's inability to speak and write had the potential to affect

many of his projects. His consulting firm, InnoSight, now employs 60

people. At Harvard Business School he had just launched a project

called the Forum for Innovation & Growth, which tapped hundreds of HBS

grads and executives to help generate and proliferate new management

theories. And he had created a think tank to tackle public policy

issues--especially health and education.

Grant

Two weeks after the stroke we went out to dinner together. We went to

the Charles Hotel restaurant Henrietta's Table and met a couple of

other friends there. We said, "Clayton, tell us exactly what

happened." [He said,] "I'm at this church meeting and I feel dizzy.

And before I know it I'm at that . . . What's that place where the

doctors get together?" And Christine said, "A hospital." "They had

tests. I had--what was the condition?" "It was a stroke, Clayton, it

was a stroke."

Clearly gone were certain vocabulary words. We were talking about the

Fed and interest rates. And not one shred of his basic intelligence

was gone. It was simply that certain words weren't there. Now, though,

if you have a conversation with him, you'll have no clue [of his

illness].

Ann

He'd call the hospital for rehab therapy or speech therapy, and they'd

say, "Our first appointment is three weeks from now." To be fair to

those doctors, they're full. Even in the hospital, within a couple

days of the stroke, he wanted to start practicing. He'd make lists of

words on a topic.

Stephen Kaufman (former CEO of Arrow Electronics, current Harvard

Business School professor)

All three of his problems [heart attack, cancer, stroke] were on the

severe side, needing the big hospital with the big tools. But the

recovery from his stroke would be representative of what can be

routinized. There's a large body of knowledge that can be used in the

therapy. It doesn't have to be done at Mass General.

Matthew

While he was waiting for speech therapy he went and bought Rosetta

Stone English. There's an image of something on the software and you

say the word. He'd have contests with my oldest daughter, Madeleine [6

years old]. He lost a lot.

Clayton

I'm an optimistic person. But for the first time in my life, with all

my problems, I focused more and more on me--and it was depressing,

literally. Sometimes I just wanted to quit trying to learn and speak

and write again and just go into my basement and build furniture. I

learned an important lesson from this. I learned that focusing on my

own problems does not bring happiness. God didn't say, "Okay. For

those with problems it's okay to focus on yourself. And for those who

don't have problems, I want you to focus on helping others." Even in

dire times God does not exempt me from his commandment to focus my

life on others, because it transforms hardship to joy.

Matthew

In the vein of kicking a man while he's down, chemo knocks out the

salivary [gland], which knocks out your calcium on your teeth. So now

he has to get implants in all four quadrants of his mouth. His

dentist, who has been wonderful, accommodated him with seven-hour

marathon sessions that include some jawbone reconstruction.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Matthew Eyring (president of Innosight, Christensen's consulting firm)

He talked to a presidential candidate or two. He's spoken to some

members of Congress and senior members of the Administration. What is

tough for him is that his insights into the health care system and

what needs to be done are truly breakthroughs--and they really work.

His disappointment is that it moves very slowly.

Clayton

I've had those meetings, but I'm unable to help Mitt Romney or Nancy

Pelosi and everybody in between. I think [my] brain is really good at

getting through the complexity. I'm not nearly as good at distilling

it into soundbites.

Dr. Hwang

The two doctors who co-wrote our book were both Democrats. Clay has

been adamant that the Obama legislation creates more problems than it

solves. Health care is very innovative in ways that we would call

sustaining. We are careful to explain that the U.S. system is the best

in the world. You'll get superior treatment. But for marginal

improvements in care you're adding tremendous costs. The concern is in

overshooting. To take care of people you need systems that are

lower-cost. We need to free up beds, free up doctors and empower

nurses.

Clayton

There's an interesting observation, I think, that would stand up to a

Ph.D. dissertation, but nobody's done it yet. Sustaining innovations

[those that add to or improve a product already in existence as

opposed to truly disruptive ones] drive inflation up at 6% to 10% a

year. So if you're working for Medtronic and you're in new-product

development, the thought process is: "We need a new product that we

can sell for higher prices and better profits to our best customers."

This isn't wrong, it's just the way the world works. At Harvard--you

look at the opulent facilities that are available to our students

compared with what it was 30 years ago. We have to keep ratcheting up

our facilities and our cafeterias. Our classrooms have padded chairs

and carpet, because if we don't keep providing more we can't compete

with Stanford. All these things drive prices up. What drives prices

down is disruptive innovation.

In health care there isn't anybody who has the scope to change

everything at once. The insurance company can work on processing paper

better. The hospital can try to improve its utilization of its

operating suites. It can try to use its MRIs better. Everybody can

optimize their piece of the system, but they can't rethink everything

in a systemic way.

What I hope is that my material can go to Washington as nonpartisan,

as just a foundation of understanding. If they have the same way to

frame the problem, then the Republicans and the Democrats should be

able to work together much better. The Americans look at Canada,

Europe and Australia, where the government is the payer. Maybe we

ought to adopt their model. And the Europeans and the Australians are

saying, "You know, this isn't working very well, maybe we ought to

adopt the U.S. model." That's the wrong categorization scheme. The

right one question is "Should we be integrated (like Kaiser Permanente

or Finland), or should we be modular (like Partners in Boston and the

Canadian and German systems)?" It's not public versus private.

Ann

I'm not sure how to describe how shocking it's been to have this

happen one after another. He is acutely aware of how lucky he is, and

I think knowing that it could have been worse has been a helpful

perspective. He's not the kind of guy who feels sorry for himself.

It's a blessing that he's alive and treatable. Our family is very

close. We've all leaned on each other a lot.

Matthew

Superficially you could say it's unfair that a guy who has worked so

hard to be healthy could be slapped with a heart attack followed by

cancer followed by a stroke. We believe there's a reason for it. But

we don't understand all of it. As this started to happen, a flood of

everything from cheerful telephone conversations to Facebook wall

posts talked about how inspiring my dad has been to them. It was

pretty humbling.

At one point in the middle of this, we were thinking of getting a

second opinion. I networked into a guy at Mayo. He was familiar with

my dad's research. He said, "Your dad has changed my life. Anything I

can do, I'll do." A lot of people when they go through near-death

experiences look at their lives and feel like they have to make big

changes. My parents in fact have not made big changes. They feel like

they're living the way they should.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Clayton

When I was at Oxford, each one of us had responsibility for three or

four families in our congregation, which we call a ward. Another

student at the university and I were assigned to look after quite a

poor family. I learned that their 10-month-old baby, Wendy, had been

in the hospital for six months. She couldn't digest anything. Wendy

had the body of a newborn, but her face looked like a 10-month-old's.

They had decided nothing could be done. So my companion and I said

let's go see Wendy, and we went there and understood the situation. I

then had a feeling in my heart, which I feel came from the Holy Ghost,

that in this case God wasn't trying to bring her home. Wendy was

sleeping. So we put our hands on her head, and through the power of

God and authority of the priesthood, blessed her. And she got better.

I don't view it as mystic. I believe that God is our father. He

created us. He is powerful because he knows everything. Therefore

everything I learn that is true makes me more like my father in

heaven. When science seems to contradict religion, then one, the

other, or both are wrong, or incomplete. Truth is not incompatible

with itself. When I benefit from science it's actually not correct for

me to say it resulted from science and not from God. They work in

concert.

Dr. Christensen Is In

Disruption is the cure for what ails health care.

Since the late 1990s Christensen has been influencing change in health

care through both his summer leadership program at Harvard Medical

School for hospital administrators and regular consulting work for

medical giants like Johnson & Johnson and Medtronic. Recently he

helped J&J develop a device that would make it easier and cheaper to

administer anesthesia. (The Food & Drug Administration rejected it.)

His book The Innovator's Prescription (2009) was co-written with two

doctors, the late Jerome Grossman, who ran Tufts Medical Center for 16

years, and Jason Hwang, a former student of Christensen's. Hwang

contributed enormously to this story.

The authors acknowledge that the fee-for-service reimbursement system,

in which providers earn more by treating patients more aggressively,

impedes the kind of disruptive innovation that would lead to better

care at a lower cost. There are several systems we could adopt that

would be better, but there isn't a road map to get there. The business

models of health are frozen in the hospital and the doctor's office.

The path to fixing the system is to disrupt those models. Here are

some approaches:

Routinization. A hospital is really three business models under one

roof, each of which manages a different type of medical practice.

Intuitive medicine is the realm of highly trained specialists handling

difficult diagnoses and treatment. Empirical medicine is the costly

realm of chronic care and trial-and-error treatment. Precision

medicine, the real goal for the system, is a case where diagnosis is

known and so is the therapy. Then treatment can be routinized and

moved off-site. Disruption will involve pushing more of medicine into

the precision category, then automating that care to make it better

and cheaper.

Consolidation. The best way to unleash disruption is if more health

care providers combine, controlling hospitals, doctors and health

insurance. Christensen makes an analogy to RCA in the 1950s. To get

people to watch the first color programming on its NBC channel, RCA

also had to manufacture color TV sets. A hospital loses money if it

tells patients to go to an outside cheaper clinic. But if it owns the

health plan and the clinic, disruptive ideas will flourish.

Precision. The kind of targeted therapies now used in cancer

treatment, such as the drug Christensen received, will be applied more

widely. Diseases will be subtyped more specifically and therapies

tailored to work better. This will also save time and money as

clinical drug trials become more focused. Specialty clinics will arise

to implant devices more cheaply.

Do-it-yourself. Christensen predicts a rise in self-diagnosis and

self-care, as tools that used to be stuck in the hospital reach

patients and their families.