How startup CEOs can optimize their funding strategies and avoid the common cash management pitfalls.

By David Skok, contributor

All smart CEO's know that they need to focus on building a compelling product, hiring a great team, maximizing sales and making their customers happy. For many first-time CEO's, focusing on these extremely important topics may distract them from another very important task: ensuring that the company can continue to raise funding at ever increasing valuations.

In practice this means that CEO's should:

- Make sure that they understand when their cash runs out

- Understand what milestones have to be achieved to get a higher valuation

- Create the right plan to achieve those milestones in the right timeframe

Managing to your cash out date introduces some very strict time deadlines into the equation, and requires you to examine which specific milestones you plan to achieve before that date.

1. Understand how startups are valued.

To understand why milestones are so important, let's take a look at how startup valuations change over time. First time entrepreneurs should be forgiven for thinking that their valuation will just increase linearly over time since their last round. After all, they have been putting in a ton of late nights and weekends working to make progress. However in practice, things typically don't work that way:

Like other investments, startup valuations are based on a calculation of risk and reward. Valuations increase as the level of risk goes down (or as the size of the perceived eventual reward goes up). In practice, risk is not reduced linearly over time, but instead changes in big increments when particular milestones are reached. These milestones could be things like customer traction, the hiring of a strong management team or, in the case of an Internet business, when a monetization strategy is proven to work.

Usually the single biggest way to show that risk is being reduced is to show evidence of increasing traction with paying customers. If a significant number of customers are willing to pay for a product, that tells an investor many positive things:

- The company has reached product/market fit

- The monetization strategy is working

- The technology works

- The team has shown some ability to execute

However this can be a hard milestone to reach on one round of funding, so investors will look for intermediate milestones that help to tell them that risk is being reduced. Here are some steps along the way to full customer traction that increasingly de-risk a startup:

- You have shown a wireframe mockup of the application to a significant number of customers and they are willing to talk to investors and tell them that they plan to buy the product when it ships.

- You have shipped a beta of the product to some customers

- Your beta customers are testing the product and reporting success

- You have a large number of free users, and their engagement with the product is high

- You have sold the product to a small number of paying customers

- Your paying customers have put the product into production usage, and are reporting success

- Your customers are coming back and re-ordering, and recommending the product to their friends

Readers of one of my earlier blog posts, Setting the Startup Accelerator Pedal, will know that I like to think of the lifecycle of a startup in three phases. The first phase is the search for product/market fit. Increasing customer traction is the best way to prove to investors that you have reached product/market fit. The second phase is the search for a repeatable and scalable sales model. Reaching this milestone will greatly increase valuation and attract growth stage investors who like to invest in companies that are ready to scale.

Once a startup enters the third phase -- scaling the business, it will usually start to see its valuation increase linearly as a multiple of revenues or profitability.

Other milestones that impact valuation are:

- Hiring a great CEO with a proven track record

- Hiring a strong management team

- Reaching profitability

- Becoming the clear market leader

2. Identify your specific risks

In the early days of a startup, the nature of the risks can vary greatly from one startup to the next. For example, if your startup is promising to deliver a new battery for electric cars that can hold 10x more energy, there is little risk that you will be able to sell the battery. Usually with this kind of startup, the major risk is whether the technology will work.

Another startup might have significant execution risk, and their valuation might increase if they are able to hire proven A player executives that have a track record of great execution. For example, if a company is started by a strong business founder, but requires great software to be developed, that startup would become both more likely to get funding, and a higher valuation, if the business founder were able to attract a proven technical co-founder.

Another type of startup might have shown great customer traction for its free product, but not yet have proven that it can figure out how to charge those customers. (e.g., the early days of Google, Twitter and Facebook.) Proving that it can monetize effectively would increase valuation.

Other startup risks include:

- Team: unproven team. Not clear if they can execute.

- Competitive: crowded marketplace with significant competitors

- Market timing: you're confident about the long term market prospects, but it is not clear when the market will take off.

3. Look for quick ways to litigate risks before fundraising

If your company is about to raise funding, and you have very little time available, there are likely some quick steps you can take to decrease investor risk, and therefore increase your chances of success, plus get a higher valuation.

- The best example of this would be a company looking to raise a Seed or Series A round. Even in this early stage of the business, any proof of customer traction can greatly de-risk your startup and increase valuation. This could be accomplished by sketching wireframes of the application, and showing them to customers. The goal would be to get enough customers to validate that this meets a real need so that they are keen to start using it as soon as it ships, and willing to pay for it. If you were able to walk into an investor meeting with a list of 20 customer that were willing to talk to investors, or had provided you with a written statement to that effect, your chances of getting funded would go up substantially, and your valuation would likely increase.

- In our battery example above, the major risk was technical. A quick way to mitigate the risk (but not totally eliminate it), would be to get the top technical expert in the particular area of science to take a look at the scientific problem you were aiming to solve, and have them render an opinion that this technical approach should work.

4. Either aise enough cash to match the milestones...

When raising a round of funding, identify the next target milestone that you'd like to reach to significantly de-risk the business. Reaching this will enable you to raise an up-round (up-round = round raised at a higher valuation than the post-money of your previous round).

As an example, let's say you have just raised your Seed or Series A round. Your next most important milestone will be ship the product and get enough customers using the product to start to demonstrate evidence that you have product/market fit. The more customers the better, and if they are paying, that is even better.

Once you have identified that milestone, do some hard thinking on how long it will take you to reach that point with some conservatism built in. Then add three months of cushion for the time it will take to meet with investors to get the next round raised.

Knowing that time frame will allow you to figure out how much money to raise.

Remember, company success is far more important than dilution. A common mistake that entrepreneurs make is to focus too heavily on avoiding dilution by raising less money. Another common problem is failure to build in enough cushion for the unexpected. It's pretty common for product development to take longer than planned, or for sales to take longer to ramp than hoped. Raising more cash to provide a cushion is often a very smart way to decrease overall dilution, as it will allow you to optimize the subsequent round.

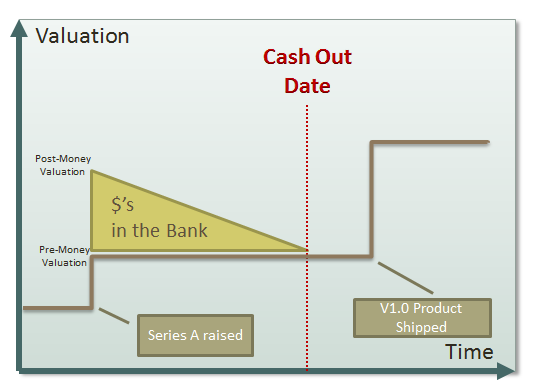

The diagram below shows where most startups fail. If you are financing to get through this zone and have any level of concern, it pays to take more cash.

5. ... or match your milestones to available cash

If you have already raised cash, you will want to figure out what milestones could be reached before you hit your cash out date. You may well find that your current strategy is targeting a milestone that cannot be completely achieved with the cash you have in hand. If that is the case, you could be setting yourself up for a down round.

The best strategy here is to do one of two things:

- Reduce your burn rate to allow you to complete the milestone before you run out of cash.

- Pick a different intermediate milestone, and ask investors if reaching that will allow you to successfully raise an up-round.

As an example of #2, let's go back to our battery company. It may have been working towards shipping the product before reading this post, but now realizes that it doesn't have enough cash runway to achieve that milestone. Investors are going to look at that company as not having de-risked the business. The solution could be to build a working prototype that proves that the technology risk has been overcome.

As another example, I have been working with several Tech Stars companies that have funding that lasts only three months. For certain types of companies, three months is enough time to build a product and get some customer traction. However for other startups, three months is not enough time to get a minimum viable product built. As are result, they will not be able to show either a finished product, or customer traction. No customer traction will make it very hard to raise their next round. They on getting customers excited enough about wire frame mock ups to tell investors that they would likely purchase the product when it finally ships. Reaching that milestone will be more important than showing a product that is not far enough along to put into customers' hands. Recognizing this can dictate a change in strategy, and help with deciding where to allocate scarce resources.

6. Validate your milestone / valuation targets with investors

Validate with investor friends that the milestones you have picked to accomplish prior to your next fund raising will be good enough to warrant the valuation increase you are hoping for.

7. Focus all energies on reaching those milestones

As a startup CEO, one of your key roles is to provide clarity and focus to the whole organization. The exercise above will bring great clarity to the milestones that the company has to achieve. Executing to these milestones should become the primary focus of the company. Don't allow yourself to get distracted! The cost of failure is usually a down round, but can sometimes result in the closing of the company.

8. Avoid down rounds at all costs

Down rounds are a serious problem for a startup. Word usually gets around that the company is not performing according to expectations, and that can have a significant negative effect on hiring, sales, etc. The damage to morale can be considerable.

Such deals also bring serious dilution. Not only are you raising money at a lower valuation, but you will also trigger the anti-dilution clause from your previous investment round.

Down rounds happen because you failed to reach the milestones needed to grow into the valuation set by the post-money of your last round. Right after closing that round, your company would have been able to justify that post-money valuation because of the cash sitting in the bank. But as that cash gets spent, your valuation will drop, unless you reach the next milestone (see diagram below).

Most of the time down rounds are caused by a failure to execute. That is why it is so important to plan correctly, and then execute according to plan. This seems so obvious that it doesn't need to be stated. However I have personally seen this problem happen over and over again. When speaking with the CEO's after the fact, most would tell you that, in retrospect, they would have lowered their burn rate, hiring fewer people, to give them the runway they needed to get to the next milestone.

Sometimes down rounds can be caused by raising money at an unrealistic valuation that can't be justified no matter how good the execution. Entrepreneurs who have lived through bubbles understand this well.

It is surprisingly easy to get a high valuation in today's funding environment because of the over supply of investors, and the shortage of supply of really interesting deals. My strong advice to entrepreneurs is to make sure that they are not setting unrealistic expectations for how they will execute, as failure to meet those expectations will come back and bite you in the next round.

If you are going to raise money at a crazy high valuation, ideally make sure it will last you through to cash flow breakeven. If you have to raise money again at a lower valuation, the negative company stigma and dilution usually far outweigh the benefits. You would have been better off to take a lower, more realistic, valuation, and be in a position to do an up round next time round.

To quote Andy Verhalen, one of the most experienced partners in our firm: "The best way to optimize for dilution is not to try to optimize a single round, but rather over the long haul (i.e. the whole series of rounds). To do this, you want to space your fund-raising after appropriate milestones (with a cushion) so that valuation increases monotonically. Serious dilution occurs in down rounds, not in slightly under-priced rounds."

Conclusion

My goal was to highlight how startup valuations change based on milestones that significantly de-risk the business. Armed with this information, entrepreneurs should talk to investors to understand how they see the risks and milestones. Then plan and manage their business around achieving desired milestones before hitting their cash out date.

The most important takeaways are:

- Take the time to think this through and build a plan.

- Make following the plan a very high priority.

I have one final comment: Success at raising money does not equal business success. I have generally found that it is far easier to raise money than it is to get paying customers. If you have just raised a round at a great valuation, don't confuse this with real success in business. That only comes from selling your product to lots of customers!

David Skok is a five time serial entrepreneur turned venture capitalist at Matrix Partners. He blogs here.